The Bank of England chose not to play follow the leader after the Federal Reserve’s 0.75 percentage point interest rate rise on Wednesday, but the UK central bank signalled that its decision was not its last word on fighting inflation.

Choosing a more modest rise of 0.5 percentage points on Thursday to put interest rates at 2.25 per cent, the BoE Monetary Policy Committee instead steadied itself for a game of tug of war with the new ministerial team running the Treasury this autumn.

The MPC made clear the rate rise was something of an interim decision because it could not factor in the probable impact of Friday’s mini-Budget by new chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, who is focused on a plan to kick-start economic growth.

The MPC minutes of its September meeting said: “All members . . . agreed that the forthcoming growth plan would provide further fiscal support and was likely to contain news that was material for the economic outlook.”

With big decisions on monetary policy postponed to November, the MPC had to strike a delicate balance at its latest meeting.

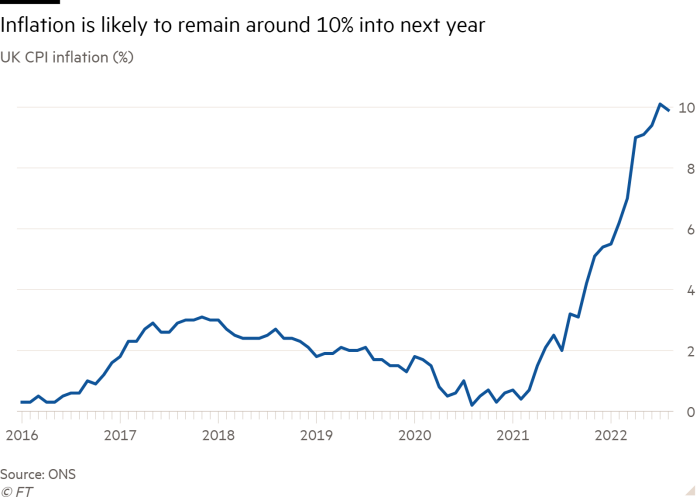

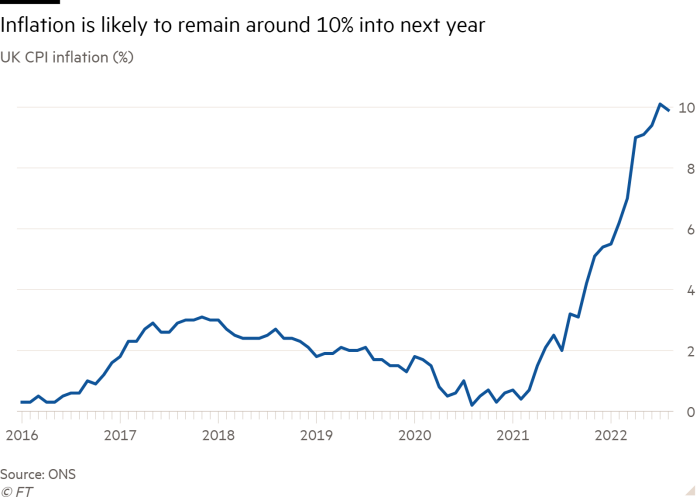

Since the BoE last published forecasts, in August, the economy has weakened — the MPC now believes it has shrunk over two consecutive quarters. Meanwhile the plans of new prime minister Liz Truss to cap energy prices for households and businesses and push through big tax cuts are likely to lower inflation in the short term, while making it more persistent later on.

These tensions were reflected in the split vote on interest rates on the nine member MPC. Five wanted a 0.5 percentage point increase, while three voted for a more aggressive rise of 0.75 percentage points. One dissented, seeking a smaller increase of 0.25 percentage points.

Most economists thought the BoE’s cautious approach, and the guarded tone of the MPC minutes, was reasonable given the difficult timing of its meeting — coming just a day before Kwarteng’s “fiscal event”.

The minutes showed that although Clare Lombardelli, chief economist at the Treasury, was present at the MPC meeting, she did not brief the committee on the government’s fiscal plans.

“The MPC seemed careful not to openly criticise fiscal policy,” said Ellie Henderson, economist at Investec, while adding the government’s planned fiscal expansion would ultimately “result in higher rates for longer”.

Allan Monks, economist at JPMorgan, said the MPC vote had been “a very close call” with recent data and a downgrade to the growth outlook having played “some role in steering the MPC away from a 0.75 percentage point hike”.

Julian Jessop, a fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think-tank, expressed disappointment at “another missed opportunity [for the BoE] to regain credibility” in fighting inflation.

But he also noted “mitigating factors”, given the BoE was pressing ahead with selling some of the government bonds it had accumulated in its quantitative easing programmes since 2009. This move was likely to raise government borrowing costs in financial markets.

Economists said markets had been reassured by the BoE’s promise that it would give a full assessment of the effects of the government’s pump priming of the economy at the MPC’s November meeting.

Sterling was stable after the latest MPC decision, albeit close to a 37-year low against the dollar, and government borrowing costs were little changed. Markets still expect the BoE to act forcefully and roughly double interest rates to well above 4 per cent by next summer.

Several economists said the most striking feature of the MPC’s decision was the three-way split on the committee.

Andrew Goodwin, at the consultancy Oxford Economics, said this suggested the MPC was now more likely to vote for a larger, 0.75 percentage point rate rise in November, adding: “With only two members needing to change their mind to tilt the balance, the bar for faster hikes is set low.” But James Smith, at ING, drew the opposite conclusion, saying the increasing division on the MPC was “a sign that market expectations are unlikely to be met”.

Ben Nabarro, UK economist at Citi, said the MPC’s November meeting would now take special prominence because it would be the last chance for the committee to demonstrate it would not let government borrowing and tax cuts keep inflation too high for too long.

“The minutes make multiple references to prime minister Truss’s fiscal plans,” he added. “We see this as a warning that further acceleration [in interest rate rises] may yet be on the cards.”

There have rarely been direct clashes between the government and the BoE since it gained independence to set interest rates in 1997.

Since becoming chancellor this month, Kwarteng has stressed the need for “co-ordination” between monetary and fiscal policy in the future but has not defined what he means by this.

But now the BoE appears to be on a collision course with the government, determined to ensure inflation comes down from the 9.9 per cent rate in August to the central bank’s 2 per cent target and that companies and workers believe it is serious.

Henry Cook, economist at MUFG bank, said the days of alignment between Treasury and the BoE were over and that was ushering in a new tension at the heart of economic policy.

“Unlike in the years following the global financial crisis, it’s now the Treasury that is supporting the economy — while policymakers at Threadneedle Street are rushing to tighten policy in an effort to rein in soaring inflation,” he added.

Credit: Source link