Dressed in a blue shirt rather than clerical garb and gaunt after nearly four months under house arrest, Bishop Rolando Álvarez sat alone in a Nicaraguan court, charged with conspiracy to undermine national integrity and spreading false news.

Last week’s appearance was his first in public since being arrested in August during a raid on his diocesan headquarters in Matagalpa, where he had been holed up with 11 colleagues in protest at Catholic media outlets being closed.

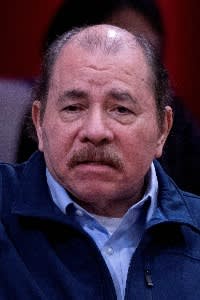

The detention of Nicaragua’s most outspoken prelate, whose trial will begin in January, has sent an unmistakable message to other opponents of the regime of President Daniel Ortega and his wife, vice-president Rosario Murillo.

“He’s been very direct and one of the few priests not afraid to speak out,” said Yader Morazán, a lawyer who fled Nicaragua in 2018. “This is about punishing him and sowing terror in the population and other clergy, too.”

The business community was cowed into silence after it voiced support for anti-government protesters in 2018. The leaders of Cosep, the main business organisation, were imprisoned. The regime has shut down more than 3,000 NGOs and forced 54 media outlets to close, according to Confidencial, a Nicaraguan newspaper operating from neighbouring Costa Rica.

Now it is stepping up its repression of the Catholic Church, which has criticised Ortega’s persecution of protesters and his authoritarian excesses, while supporting the families of political prisoners.

“It has the objective of closing the last remaining civic space in the country, which is the space for freedom of conscience, freedom of preaching, religious freedom, even of the church,” said Carlos Chamorro, director of Confidencial.

The persecution of Álvarez and the church comes as Ortega and Murillo consolidate power and imprison opponents. The ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front swept all 153 municipalities in elections last month that the US called “a pantomime”.

The regime continues to hold 225 political prisoners, including “relatives of detained political opponents, allegedly to coerce the latter into surrendering,” the UN high commissioner for human rights Volker Türk said last week.

“It’s on the way to becoming a virtual North Korea in Central America,” said Tiziano Breda, Central America analyst for the International Crisis Group. “It’s a country where Ortega has reckoned that, to maintain control of the state and to remain in power, the only way to do it is through total suppression of any minimal dissident voice.”

Ortega and Murillo have routinely condemned bishops as “terrorists” and “coup mongers”. Police have thwarted feast-day processions and officers routinely patrol outside churches in acts of intimidation, according to priests.

The Missionaries of Charity, the order founded by Mother Teresa, left in July after losing its registration. The Vatican’s ambassador, Archbishop Waldemar Sommertag, was expelled in March.

“The last institution left standing as a beacon of hope was the church,” said an exiled priest, who requested anonymity for security reasons.

The church has had a chequered relationship with Ortega since he first became president in 1979 when the Sandinistas ousted Anastasio Somoza. Ortega lost power in 1990, but regained office in 2007, presenting himself as a proper Catholic and courting close relations with the church hierarchy, according to analysts.

Ortega and Murillo married in a Catholic ceremony in 2005. He later backed a draconian abortion law in 2006, passed two weeks before an election he won, which bans the procedure in all circumstances.

“[The bishops] were distracted by this effort by the Ortegas to crack down on abortion and they didn’t see the rest of the picture,” said Ryan Berg, director of the Americas programme at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think-tank.

“Ortega uses the Catholic Church as a kind of useful device if he needs it and like a carpet if he needs to lay the blame somewhere.”

The church became an outspoken Ortega critic after protests erupted in 2018 over proposed social security reform.

Priests opened their parishes to wounded protesters being pursued by police and paramilitaries. The bishops’ conference convened a national dialogue to find an exit from the protests and political crisis but then withdrew, alleging bad faith on the government side.

Pope Francis has spoken tepidly on Nicaragua. He expressed concern after Álvarez’s arrest in August and called for dialogue. He said in a press conference the following month: “There is dialogue. That doesn’t mean we approve of everything the government is doing or disapprove of it.”

Analysts say dialogue between the government and protesters has gone from trying to find a political solution to the 2018 protests to simply seeking to improve conditions for prisoners held in El Chipote prison, on the outskirts of the capital, Managua.

“Dialogue doesn’t make sense with the dictatorship because it’s holding participants from the first dialogue in prison,” said Father Edwin Román, a Nicaraguan priest exiled in Miami.

“I don’t think the Catholic Church will lend itself to another circus, when there’s a bishop and priests imprisoned.”

The Nicaraguan bishops’ conference has remained silent on Álvarez’s arrest. It did not respond to a request for comment.

“The bishops have opted for silence and prayer and not mentioning the problem to not be persecuted,” said the exiled priest.

“This is not seen well by a demoralised people . . . asking that something be done and that the bishop be defended.”

The exiled priest said he knew of 11 imprisoned priests, including Álvarez, along with two seminarians. An unknown number have fled or been expelled. Murillo, the government spokesperson, did not accept an interview request, but said in a short statement: “Together, we are going to move ahead with our heads held high!”

Álvarez repeatedly refused to flee the country prior to his arrest.

“Bishop Rolando Álvarez prefers to stay in Nicaragua, although a prisoner, and not go free to another country,” said Bishop José Antonio Canales of Danlí, Honduras, who knows Álvarez. “He’s a very brave and decisive man.”

Credit: Source link