Receive free Visual and data journalism updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Visual and data journalism news every morning.

The number of people killed by police each year is significantly higher in the US than in other developed nations, even when accounting for countries’ population sizes.

US levels of per capita law enforcement are much higher, for example, than France, where the fatal shooting of a 17-year-old boy has led to civil unrest.

However, there are significant caveats when comparing police killings by country — the metric is counted differently in some countries owing to inconsistencies in how deaths caused by police are defined.

Many states also lack official annual records of law enforcement killings, meaning the data has to be pieced together from different sources and is not always available for the same year.

Felix Wallis

Our other charts of the week

There has been a 99 per cent fall in poppy production in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, according to new satellite analysis by geospatial company Alcis. The region previously grew more than half of the country’s opium.

The unprecedented fall in cultivation follows the Taliban’s decision to prohibit the growing of poppies for opium in April last year.

Although Afghanistan supplies the majority of the world’s illegal heroin, the fall in this year’s production is unlikely to have a significant effect on international supplies given there is so much opium still in the country and along trafficking routes.

However, it is not only opium production that has declined. The total amount of active agriculture in Helmand is down to 205,000 hectares this year — a fall of around 40,000 hectares from the last two years and of 65,000 from 2020.

“We think a large part of it has been held back for spring crops, like cotton, which would bring diversification to help cope with the opium ban”, Richard Brittan, founder and managing director of Alcis, said.

“But some will be left fallow, due to a lack of confidence in making decent returns for available markets.”

Sam Joiner

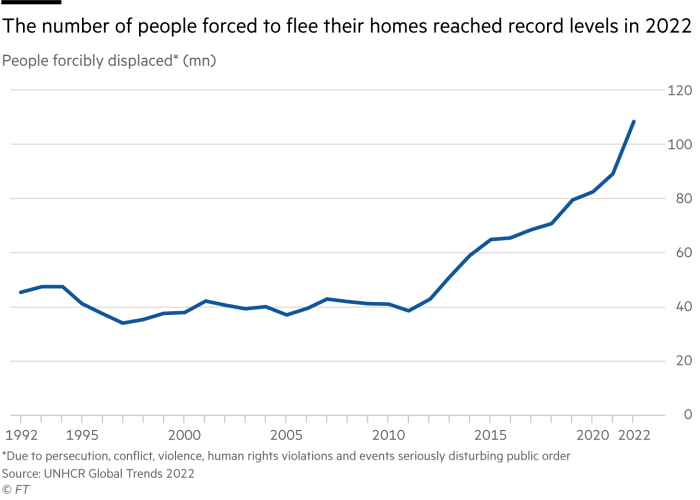

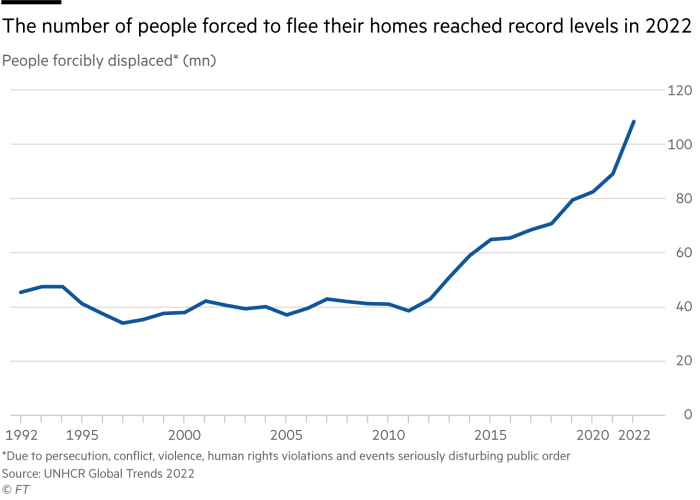

More than one in every 74 people on Earth was forced to flee in 2022, up from one in 142 a decade ago, according to the UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency.

The global number of displaced people increased by more than a fifth to an estimated 108.4mn last year.

About 58 per cent of this total were people who were internally displaced — those forced to leave their homes but remain within the same country — and a third were refugees.

Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion made up 16 per cent of all refugees and other people in need of international protection at the end of 2022, according to UNHCR.

Liz Faunce and Amy Borrett

Children in immigrant households are more likely to live in poverty than their peers in native-born households, according to the OECD. Poverty rates for children in immigrant households are still twice that of native-born households in more than half of all EU and OECD countries, despite a slight decline in child poverty in immigrant households over the past decade.

The biggest disparity is in Spain, where 62.4 per cent of children in immigrant households live below the country’s poverty threshold, compared with 19.8 per cent of children in native-born households.

Germany has seen the biggest fall in child poverty in immigrant households in the past 10 years.

Emma Lewis

There is a more than 50 per cent chance that the El Niño weather phenomenon that warms the Pacific Ocean will become a strong event by the end of the year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A strong event means it will have an impact on the global climate, such as changes in temperature and rainfall patterns.

Areas in northern US and Canada become drier and warmer while in Australia, Indonesia and parts of southern Asia there is a greater chance of drought and wildfires.

El Niño is also associated with more rainfall in parts of southern South America, central Asia and the Horn of Africa. The south-east US and Gulf Coast are wetter, too, with an increased risk of flooding.

Globally, the warmest year on record was in 2016 following a strong El Niño event that began in 2015.

Chris Campbell

The median range of electric vehicles has caught up with Tesla’s cars, while there is a widening gap between the US carmaker and the longest-range EVs, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

The company’s range dominance contributed to its market value surpassing $1tn in 2021, which was, at the time, greater than its top five competitors combined. However, luxury EVs such as Lucid Air have since eclipsed the long-distance capabilities of Tesla’s cars.

According to Elon Musk, the additional battery mass required for longer-range vehicles degrades their acceleration, handling and efficiency.

As a result, Tesla has given up pursuing range supremacy and is focusing on autonomous driving to distinguish its cars in an increasingly competitive EV market.

Felix Wallis

Welcome to Datawatch — regular readers of the print edition of the Financial Times might recognise it from its weekday home on the front page.

Do you have thoughts on any of the charts featured this week — or any other data that has caught your eye in the past seven days? Let us know in the comments.

Keep up to date with the latest visual and data journalism from the Financial Times:

-

Data Points. The weekly column from the FT’s chief data reporter John Burn-Murdoch.

-

Climate Graphic of the Week is published every week on our Climate Capital hub page.

-

Sign up to The Climate Graphic: Explained newsletter, free for FT subscribers. Sent out every Sunday, a behind-the-scenes look at the most topical climate data of the week from our specialist climate reporting and data visualisation team.

-

Follow the FT on Instagram for charts and visuals from significant stories.

-

Follow FT Data on Twitter for news graphics and data-driven stories from across the FT.

Credit: Source link