It starts with drugs, says John. Paramilitaries in his working-class area near Belfast control the trade. Young teenagers go to them for weed and cocaine, but soon they are hooked and have racked up a “strap”, or debt. They struggle to pay because they can’t get a job until they are 16, so they are given two choices, he says: “take a punishment beating, or sign up”.

The first option can be anything from being set upon by a group of men to being hit by baseball bats studded with nails. Signing up requires members to pay weekly dues that locals say can range from around £5 a week to £20 for people in work.

“It’s weird — it’s sort of normal to know it happens. You can’t really try to stop it,” says John, a youth worker in his 20s who asked not to use his real name. A love of sport meant John stayed away from drugs but his best friend, who had a habit, ended up joining the paramilitaries.

“If you sign up, you get taken to a house, you put your hand on a Bible and swear to the cause. There are a couple of masked men there, and flags,” he says. The main groups, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), were involved in Northern Ireland’s three decades-long “Troubles” in the name of loyalism: defending Northern Ireland’s place in the UK.

The conflict ended 25 years ago on April 10 1998, with the Good Friday Agreement; US president Joe Biden is visiting Northern Ireland next week to celebrate the historic peace deal.

But while the Irish Republican Army gave up its long war to oust British rule in Northern Ireland, loyalist paramilitaries have failed to disband and still have an estimated 12,500 members. Instead, loyalist organisations in Protestant communities have morphed into something “much more akin to organised crime and even mafia groups — for profit and criminal gain rather than any political motive”, says Colm Walsh, a research fellow at the school of social sciences, education and social work at Queen’s University in Belfast.

At the same time in some Catholic communities, small splinter IRA groups that rejected the Good Friday deal as a sell-out continue their armed struggle, albeit on a far smaller scale.

The result is that even after more than two decades of relative peace, the threat of political violence has never completely disappeared. Far from becoming a reconciled society that has left the past behind, Northern Ireland has almost normalised the presence of paramilitaries within society.

“They’ll [the loyalist paramilitaries] never go away because they’re always making money and they’re always in control of what’s happening,” says one former UVF member, now 45 who has both received and doled out the beatings and shootings — usually in the legs, known as “kneecapping” — that paramilitaries still use to intimidate and coerce people.

“The peace process has allowed us to deal with obvious violence like bombings and shootings, but we’re still getting to grips with the hidden harms carried out by paramilitaries, like child criminal exploitation, abuse of women, coercive control, economic crime, extortion and gatekeeping,” says Adele Brown, director of the Northern Ireland executive’s Tackling Paramilitarism, Criminality and Organised Crime Programme.

Brown calls paramilitary attacks on people a “pervasive, but relatively localised phenomenon”. But according to government data, 15 to 30 per cent of people in Northern Ireland have been affected by “paramilitary harm” and police say 32 per per cent of organised crime has direct paramilitary links.

Since the Paramilitary Crime Task Force began operations in late 2017, police have seized £3.75mn of controlled drugs.

Beyond the violent public attacks, the paramilitaries’ grip on communities risks poisoning the future for a new generation born into what was supposed to be peace. “Who wants to talk about the fact that they are in drug debt or have been sexually abused or are taking drugs to self-soothe because they’ve had a horrendous childhood?” Brown asks.

Chilling reminders

As Northern Ireland prepares to mark the Good Friday anniversary, tactics reminiscent of the Troubles have flared in recent weeks.

A feud between rival drug factions linked to the UDA triggered a spate of petrol bombings on properties including a house in Donaghadee, a pretty seaside town that days earlier had been declared the best place to live in Northern Ireland.

An even more chilling reminder of the kind of horrors that the agreement was supposed to have ended came in late February, this time from a dissident republican group, the New IRA. Two gunmen fired 10 shots at point-blank range at off-duty police Detective Chief Inspector John Caldwell after he had coached a football training session, seriously injuring him in front of his young son and other children.

The New IRA is perhaps best known for the murder of journalist Lyra McKee in 2019, who was killed when a bullet aimed at police hit her in the head. The group has staged sporadic attacks in its continued struggle for a reunited, socialist Ireland.

“That’s where they see their power . . . they could strike at any time, anywhere,” says Marisa McGlinchey, assistant professor in political science at Coventry University and author of Unfinished Business: the Politics of ‘Dissident’ Irish Republicanism. McGlinchey estimates the number of those involved in armed actions only runs into the dozens.

In the wake of the attack on Caldwell, the UK intelligence service MI5 last week responded by increasing the terror alert in Northern Ireland to “severe”, indicating an attack was “highly likely”.

As Sandra Peake, head of the Wave Trauma Centre which supports physically and psychologically injured victims of Northern Ireland’s conflict put it, the attack on Caldwell “takes people back very quickly to the feeling that they are under threat”.

Revulsion at Caldwell’s attempted murder contrasts with what amounts to a public blind eye to, or at least tolerance of, loyalist gangs and their impact on communities. Brown, of the executive programme, calls the groups “parasitic” and notes that gangs cooperate across the sectarian divide “when it’s in their criminal interests”.

But some communities turn to paramilitaries to sort out problems, either because policing is too slow or because they do not trust them.

“For many communities it’s not as easy as saying ‘get rid of them’. Their relationship with armed groups is complex,” Brown says. “Research shows that in some areas people feel safe even though these groups are carrying out crimes against their own communities.”

The more threatened a community feels, the more likely it is to turn to paramilitaries, says Walsh of Queen’s University. He notes that one community in Newtownards, the scene of the current drug feud, appealed to a loyalist group to drive out a splinter group it blamed for attacks, including one at a shopping centre in broad daylight.

Given the prevalent violence, it is hardly surprising that just half of the cases Wave works on actually date from the 1970s-90s during the Troubles themselves. “The rest will be from more recent traumatic incidents,” Peake says.

‘Flags of convenience’

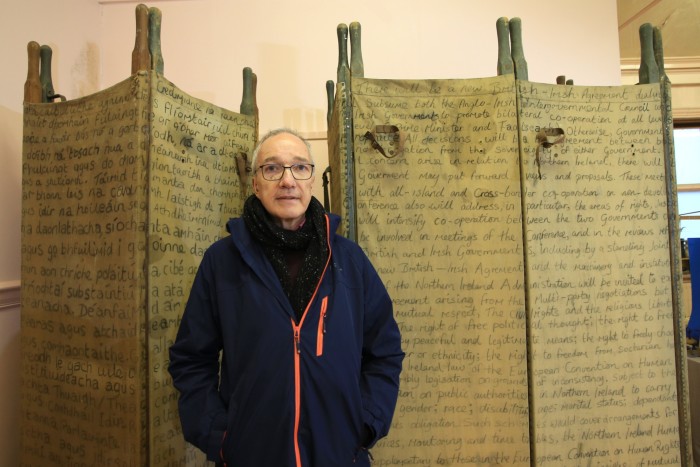

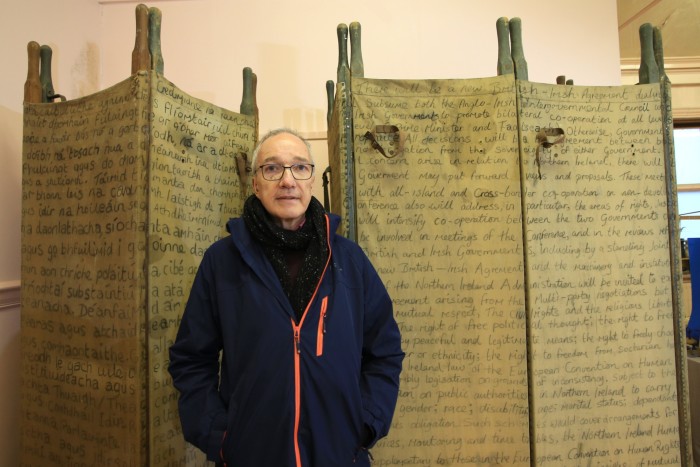

Standing in the street in the loyalist Old Park district of North Belfast, Quintin Oliver looks down the hill to the green copper dome of Belfast City Hall. “It’s a mile away, but it may just as well be a different planet,” he says.

While the city centre’s vibrant restaurant, hotel and bar scene is unrecognisable from when security gates known as the “Ring of Steel” encircled it during the Troubles, Old Park looks depressing and dingy, almost like time has stood still.

The Ebenezer Gospel Hall, across from where Oliver stands, still bears the same quotations from the scriptures on its wall as it did in the early days of the Troubles. “Peace walls” nearby still separate traditional unionist and nationalist communities, reinforcing enduring divisions in a society where education is still largely segregated and Protestants and Catholics sometimes even choose different bus stops.

Oliver, a political consultant who directed the “Yes” campaign in a referendum held in May 1998 in which Northern Ireland endorsed the Good Friday Agreement by 71.1 per cent, thinks it is “unhelpful” to characterise paramilitaries as just drug gangs.

He says the region “has allowed a two-speed society to develop: working-class, and everyone else”. The decline of communities — where local shops have been lost and traditional shipyard, manufacturing and factory jobs have disappeared — created a void paramilitaries could fill.

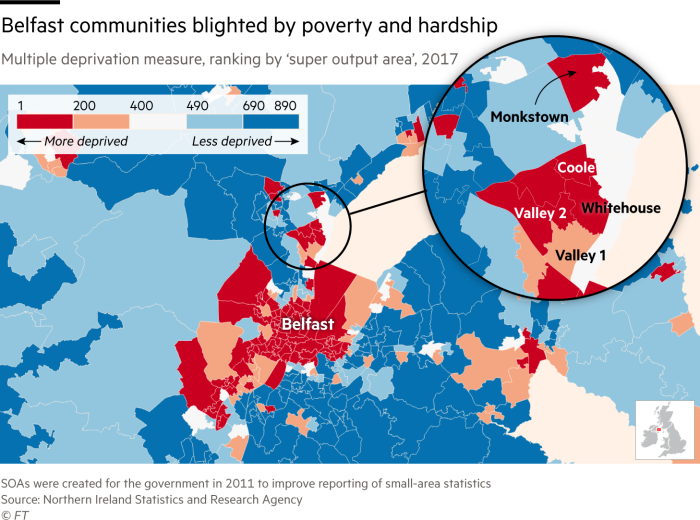

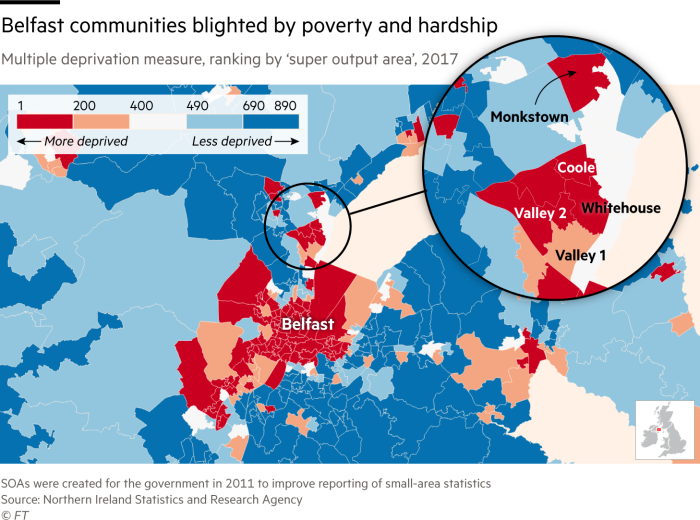

In 2015, Oliver bought the derelict Old Park library, the first of the three established by Scottish-American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie in Belfast. “All three were in the most deprived wards in the first decade of the 1900s, and still are now,” he says. “That’s the tragic bit.”

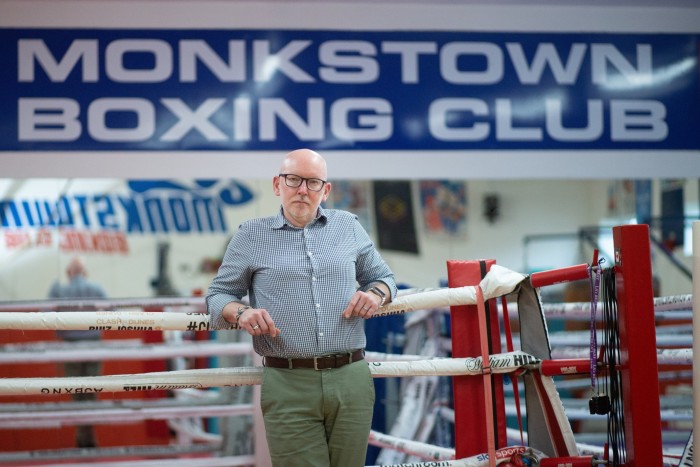

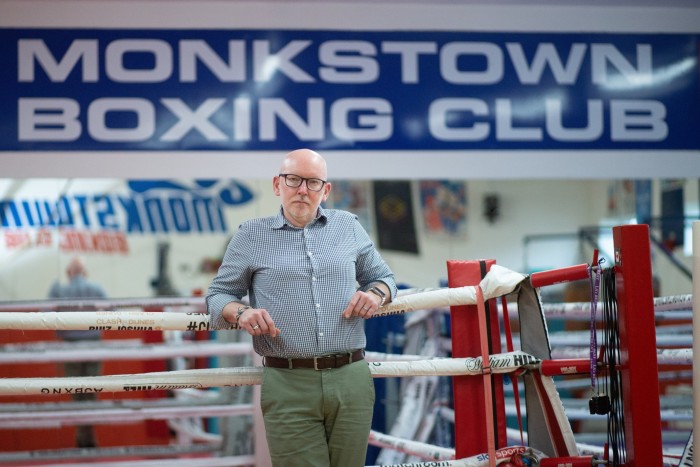

Frustration at enduring economic inequality is something Paul Johnston can relate to. As project manager at the Monkstown Boxing Club, which also runs an award-winning project called “In Your Corner” focusing on education and sport for local youths, he works in an estate controlled by the South East Antrim UDA, a breakaway faction of the main UDA and the main criminal gang for drugs in the area. Its local boss, who is 23, was not even born during the Troubles.

“We are in the bottom of most deprived communities but one mile up the road, Jordanstown is one of the top 3 per cent most affluent in Northern Ireland,” Johnston says. The consequences are stark: life expectancy in Monkstown is 10-15 years lower, he says. “This community hasn’t seen a peace dividend: 70 per cent don’t have level two [high school] qualifications and more than 50 per cent are economically inactive — it’s shocking”.

The situation is similar in some nationalist areas. But whereas Sinn Féin, Northern Ireland’s biggest party that was once the mouthpiece of the IRA, has been “very smart and tactical at bringing their people into the fold and selling the benefits of peace, we [in working-class Protestant, unionist and loyalist communities] never had that leadership to bring paramilitaries in from the cold,” says Johnston, who was born in 1969, the year most observers say the Troubles began.

He says crime gangs use the banner of loyalist paramilitaries as a “flag of convenience”. In areas where there is little trust in the police, gangs step into the role of community enforcers “because they get things done quickly”.

Funding for neighbourhood policing is set to be cut because of a financial crisis in the region and the budget from Northern Ireland’s Department of Education for Johnston’s programme is only confirmed for another year.

That will make it harder to give opportunities to a new generation of youths, like Mark, a tough-talking 15-year-old, who was almost expelled from school at 13, or William, 16, who used to enjoy recreational rioting against Catholics. Both youths, whose names have been altered to protect them, say Monkstown Boxing Club’s “In Your Corner” programme has boosted their prospects. But as for the presence of paramilitaries: “It’ll never change, so it won’t,” said William. “It’s just the world we live in.”

Culture of violence

One of the ironies of the Good Friday Agreement was that it essentially marked a defeat for republicanism and a victory for loyalism, yet each side behaves as if the opposite were the case. Not only did the IRA end its armed campaign, it acknowledged that Northern Ireland was part of the UK and would remain so until a majority in the region decided otherwise.

But Sinn Féin has reinvented itself politically while “loyalism continually feels like it’s losing,” says Paul Smyth, executive director of Politics In Action, an NGO. He also belongs to the Stop Attacks forum seeking to end paramilitary violence, intimidation and coercive control — behaviours he says should be recognised as human rights abuses, not “punishment”.

Nationalists outpolled unionists for the first time to win last May’s Northern Ireland elections, and Catholics now outnumber Protestants in the region. Smyth says loyalists constantly feel their identity is under threat. “They feel a deep sense of loss,” he says.

“Let’s be honest, the Good Friday Agreement was all about allowing republicans to carry on their goal of a united Ireland as long as they didn’t bomb,” argues Kenny Blair, a former loyalist prisoner involved in a restorative justice project in Ballymoney, Co Antrim. “We were always collateral damage over here [in loyalism].”

Brexit has infuriated the loyalist community. Ireland’s then foreign minister Simon Coveney had to be bundled off the stage at a peace-building event in Belfast a year ago after a van driver was forced to take what he believed was a bomb to the location. Police suspected the UVF in what turned out to be a hoax.

Predominantly loyalist groups were also behind the worst street violence for years in Northern Ireland, in 2021, against former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s trade arrangements for the region, the Northern Ireland protocol. Megan Phair, of Stop Attacks, told a Westminster committee earlier this year that youths had been coerced by paramilitaries into rioting to pay off drug debts.

The Independent Reporting Commission, which monitors progress on tackling paramilitarism, warned in a report in December that such groups represented a “clear and present danger” in Northern Ireland and an independent person should be appointed to help them transition away from violence — something the UK is considering.

But David Campbell, chairman of the Loyalist Communities Council, an umbrella group for the main paramilitary groups, sees a “naivety about hoping for disbandment”, saying groups who left would immediately be replaced by others claiming their mantle.

Meanwhile, political pressures remain on loyalism. Hardline unionists insist the newly revamped protocol, known as the Windsor framework, still undermines their place within the UK and the Democratic Unionist party, the region’s biggest pro-UK force, has been paralysing Northern Ireland’s political institutions for nearly a year over the issue.

“We see a lot of young people who are not interested in the Troubles yet they still want to riot,” says one community worker in a loyalist part of North Belfast. “Investment [in communities] is key, but with a non-functioning government, I don’t know what’s going to happen,” she says.

Smyth of Politics in Action says Northern Ireland still has a “very toxic culture of violence” that he fears could flare if Ireland heads for reunification.

Despite the celebrations at the peace deal’s anniversary, he admits to “a lot of angst because I feel we’ve let a lot of people down”.

“No one had the resources, the international goodwill that we’ve had. There is no one with any serious power trying to keep the conflict going,” he says. “And yet we’ve made such tiny steps.”

Cartography by Steven Bernard

Credit: Source link