When, out of frailty, Pelé withdrew from lighting the cauldron at the 2016 Summer Olympics — held for the first time in his native Brazil — it came as a signal to the footballer’s fans worldwide that they should prepare for his demise. More than six years later, that moment has come at the age of 82.

In a 21-year career, he was part of three World Cup wins. In those and in lesser matches, he hardly ever failed to score: according to Fifa, his goal tally was more than 1,200. Yet the bare statistics do scant justice to the scale of Pelé’s achievements, and the talent of a man voted best athlete of the 20th century by the world’s National Olympic Committees, even though he never took part in an Olympics.

Masterful in control of the ball with either foot, fast and strong, and a small man who could outjump bigger ones, he had all the physical attributes desirable in a footballer. Above all, though, he had perfect control of the ball and could read the field in an instant. He even invented the art of giving a pass off his opponents’ ankles. As Armando Nogueira, a Brazilian football writer, once put it: “If Pelé hadn’t been born a man, he would have been born a ball.”

Yet a ball was a luxury in the early life of Edson Arantes do Nascimento. Born into poverty on October 23 1940 in Tres Corações, a town in the inland state of Minas Gerais, he had to practise his skills by kicking a grapefruit.

The youthful Edson — even he was unsure how he picked up the nickname Pelé — dreamt of being a pilot. But when the family moved to Bauru, closer to São Paulo, he came under the wing of Waldemar de Brito, the former international who recognised that he had a phenomenon in his charge. He took the boy to Santos, a team based in the commercial capital. Not yet 16, Pelé made his debut, coming on as a substitute and scoring.

Less than a year later on July 7 1957, he played his first game for Brazil, against Argentina. Once more he was a substitute; once more he came on and scored. When the two sides met again a few days later, he was on from the start — and again he found the goal.

He nearly missed the 1958 World Cup in Sweden — a knee injury had put his place in jeopardy — but the 17-year-old put two past the host nation in the final. The brilliance of his displays and his unashamed tears of joy after Brazil’s 5-2 win established him as a global celebrity.

Four years later, physically stronger and mentally more mature, Pelé was undoubtedly the world’s best footballer. But he played little part in Brazil’s successful defence of their title in Chile. In the second match, he tore a muscle and sat out the rest of the competition.

An anxiety to show he had lost nothing inspired stellar performances at club level. Santos were contesting the world club championship with Benfica of Portugal. A 3-2 win in the first leg in Brazil was seen as a narrow lead to defend in Lisbon. Pelé confounded that view when he scored three quick goals.

Yet in the 1966 World Cup, Brazil was eliminated early. Pelé cut a forlorn figure as he trudged from the field, a coat pulled over his bare shoulders to protect him from the cool English summer. It was three years before he once more donned the yellow shirt — but from then he prepared to make Mexico 1970 his celebratory farewell to the biggest stage in sport.

At 29, he was at the height of his powers. In the final, he put Brazil on the path to victory with an awe-inspiring header. “We jumped together,” recalled Tarcisio Burgnich, the unfortunate Italian who had to mark him. “But when I landed, I saw that he was still floating in the air.” His slotted pass for Carlos Alberto to blast home Brazil’s fourth goal remains one of football’s enduring images.

Pelé remains the only man to have won three World Cups. Brazil’s three victories played an important role in the creation of a national identity in the giant country of immigrants, indigenous people and descendants of slaves. Pelé was the symbol of success, a point of unanimity in a land of regional rivalries. Although from São Paulo, Santos often staged big games in Rio de Janeiro and received impassioned support. It was fitting that Pelé’s 1,000th goal, in 1969, was scored in that city’s Maracanã stadium.

Five years earlier, a nationalist military dictatorship had seized power. As repression increased towards the end of the 1970s, the government made full use of Pelé’s propaganda potential. Pelé went along with it, telling the foreign press in 1972: “Brazil is a liberal country, a land of happiness. We are a free people. Our leaders know what is best for us and govern us with tolerance and patriotism.”

As he slowly withdrew from the pressures of competitive football, there was time and space in his life for his views to develop. In 1984, he became involved in a campaign for direct elections to the presidency. Ten years later, with democracy reinstated, he was made sports minister in the administration of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Seemingly motivated by the realisation that he had done little constructive with his earlier influence, Pelé launched a law designed to clean up Brazilian football.

That spell at the ministry was an interruption from his business activities. As a player, he had not earned the sums that his talent warranted, and having grown up poor, he was determined to achieve wealth. Pelé’s worldwide appeal made him attractive to multinationals; he signed lucrative deals with Pepsi and Mastercard, and had his own marketing company. Twice divorced, he is survived by his third wife, Marcia, and a number of children from various unions.

In his final years, the star cut a low profile, with regular hospital visits in São Paulo for cancer treatment. In September 2021, he had a tumour removed from his colon.

He posted frequently on social media and was enthused by the beginning of the World Cup. On December 1, upon admission to the hospital, he thanked fans for sending “good energy”.

“Everything I have and everything I am I owe to football,” Pelé had said in 1997.

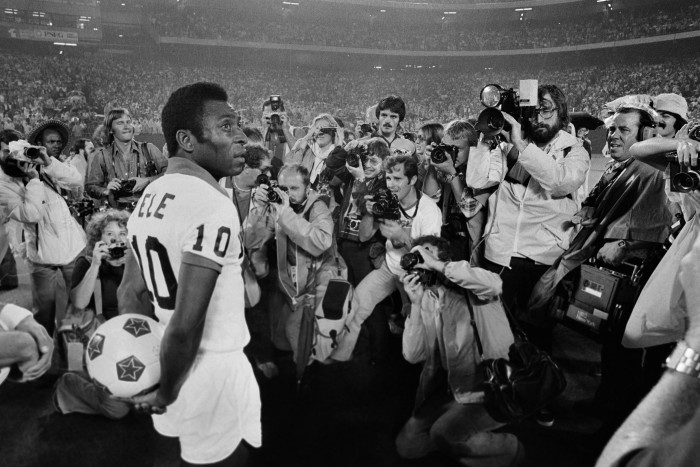

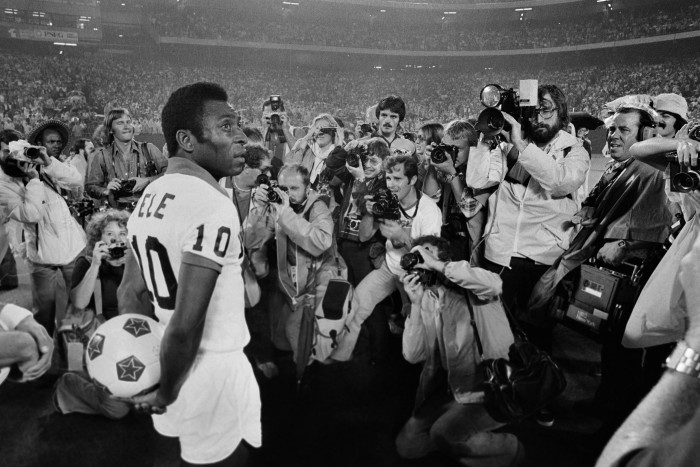

Throughout his career, he was ready to sign autographs and clearly derived and transmitted great joy in his own talent. But the joy he gave was many times vaster.

Credit: Source link